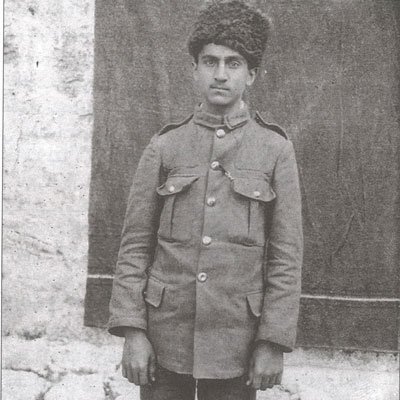

Najati Sidqi

نجاتي صدقي

Najati Sidqi was born in Jerusalem. His father, Bakr Sidqi, was a teacher of Turkish and a lover of music, painting, and the theater. His mother, Nazira Murad, hailed from Jerusalem. He had one brother, Ahmad.

He married a Ukrainian Jewish woman, named Lutka, while he was in Russia; they had two daughters, Dawlat and Hind, and one son, Sa‘id.

His paternal grandfather was an officer in the Ottoman army holding the rank of Alay Amini, who in the late nineteenth century went first to Damascus and then to Beirut and finally settled in Jerusalem.

Najati Sidqi completed his elementary school education at the Salahiyya School in Jerusalem; then he attended the Ma’muniyya, Rashidiyya and Maktab Sultani schools. When World War I ended, he accompanied his father, an officer in the forces of the Emir Faisal, to Hijaz as part of a force sent there to fight the Wahhabis. When that expedition failed, he returned with his father, who had left military service, to Syria and then to Egypt. In Cairo, the young Najati discovered modern theater, especially the Rihani theatrical troupe.

Najati Sidqi returned with his father to Jerusalem where in 1924, and after the British occupation, he worked in the Department of Posts and Telegraphs. There he became acquainted with the communist movement, which some Jewish immigrants had established in Palestine, and he joined the party.

In September 1925, the leadership of the Palestine Communist Party sent him to Moscow to study at the Communist University for Workers of the East, known as KUTV. This university prepared communist party cadres in eastern countries to assume leadership positions in their parties.

Sidqi spent three years at that university, and after mastering Russian, he studied materialist philosophy, political economy, and the history of revolutionary parties. Since then, Sidqi came to be known in international communist circles by his party name (Mustafa Sa‘di). Having submitted a graduation thesis entitled “The Arab National Movement from the Constitutional Revolution to the period of the National Front” in February 1929, he returned to Palestine with his Ukrainian wife and daughter, Dawlat, at the request of the Comintern. He was tasked with helping to Arabize the Palestine Communist Party, most of whose members were new Jewish immigrants.

The Seventh Party Congress, held in Jerusalem in December 1930, elected him a member of the party’s central committee and asked him to contribute to editing ilal-amam (Forward), the party’s clandestine newspaper.

In February 1931, the British authorities arrested him along with his comrade Mahmoud al-Atrash al-Mughrabi, and they were sentenced to two years in prison, spent in the Central Jerusalem prison, the Jaffa prison, and the Acre fortress prison. Following his release he was kept under police surveillance for six months.

In June 1933, the Comintern sent him to Paris to edit an Arabic monthly magazine (al-Sharq al-Arabi; The Arab East). The first issue came out in September of that year and was distributed in secret in a number of Arab countries, until the French government decided to shut it down in early summer 1936. In Paris, Sidqi began to write short stories.

Following the closure of the magazine, Sidqi moved to Moscow at the request of the Comintern and then went to Tashkent to study the Soviet experience in handling the “national issue.” In August 1936, the Comintern sent him to Spain where a civil war had erupted between the Republicans and the followers of General Francisco Franco. The aim was to undertake propaganda among the Moroccan troops fighting alongside Franco.

In late December 1936, Sidqi was dispatched to Algeria to take part in setting up an Arabic radio station broadcasting to North Africa in general, and to Spanish-controlled regions in particular, but the project was a failure.

Sidqi returned to France and then, in April 1937, he moved to Syria and Lebanon. There, he began to be active in the communist circles in Damascus and Beirut, and he published his articles in the Syro-Lebanese communist party newspaper Sawt al-Sha‘b and in the magazine al-Tali‘a.

Following organizational disputes between him and some leaders of the Syro-Lebanese communist party, Sidqi’s party activity was suspended. To earn a living, he turned to journalism and worked for the Beirut newspaper al-Nahar and the magazines al-Jumhur and al-Marahil al-Musawwara.

Sidqi was critical of the German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact of August 1939. So the leadership of the Syro-Lebanese communist party decided to expel him from the party.

In 1939, Sidqi returned to Jerusalem where he worked in the Near East Broadcasting Service run by the British authorities. He then began to focus his activity on literature, publishing short stories in Beirut journals like al-Adib and in Cairo journals like al-Risala and al-Kitab. He also published two books in the series called Iqra’, published by Dar al-Ma‘arif in Cairo: Pushkin (1945) and Chekov (1947).

After the Palestinian Nakba in 1948, the radio station moved to Cyprus and Sidqi moved with it, living in Limassol until 1950. He then went to Beirut to resume his career in journalism, translation, and literary and intellectual matters. In 1976, Sidqi moved to Athens where his daughter Hind was living. He died there in 1979 and was buried in that city.

Najati Sidqi was a progressive man, steadfast in his principles, committed to a cause, widely read, and gentle in manners. He was one of the most prominent Arab leftists, a brilliant man of letters and a successful translator from Russian and English. He was particularly well-known for his short stories and was among the most important representatives of realism in Arabic fiction. In addition to his prolific literary production, Sidqi wrote very interesting memoirs, which were prepared for publication and introduced by Hanna Abu Hanna.

Selected Works

"التقاليد الإسلامية والمبادئ النازية هل تتفقان". بيروت: دار الكشاف، 1940.

[Islamic Traditions and Nazi Principles: Do They Agree?]

"بوشكين أمير شعراء روسيا". القاهرة: دار المعارف، سلسلة اقرأ، 1945.

[Pushkin, Prince of Russian Poets]

"تشيخوف". القاهرة: دار المعارف، سلسلة اقرأ، 1947.

[Chekov]

"الأخوات الحزينات" (قصص). القاهرة: دار المعارف، 1953.

[The Sad Sisters (short stories)]

"مكسيم غوركي". القاهرة: دار المعارف، سلسلة اقرأ، 1956.

[Maxim Gorky]

"الشيوعي المليونير" (قصص). القاهرة: دار المعارف، 1962.

[The Communist Millionaire (short stories)].

Translations

Selected Stories from Russian Literature. Beirut: Dar Beirut, 1952.

Selected Stories from Spanish Literature. Beirut: Dar Beirut l-il-tiba‘a w-al-nashr. 1953.

Selected Stories from Chinese Literature. Beirut: Dar Beirut li-l-tiba‘a w-al-nashr. 1954.

The Golden Bug: Thirteen Stories by the American Writer Edgar Allan Poe. Beirut: Dar al-kitab, 1954.

Prosper Mérimée, Carmen (a novel). Beirut: Dar ‘uwaydat, 1957.

Sources

أبو هشهش، إبراهيم محمد. "نجاتي صدقي: حياته وأدبه (1905-1979)". القدس: الجمعية الفلسطينية الأكاديمية للشؤون الدولية، 1990.

أسعد، منى. "نجاتي صدقي أديب ومفكر سياسي". دمشق: دار المبتدأ للطباعة والنشر، 1992.

ديكان-واصف، سارة. "معجم الكتّاب الفلسطينيين". باريس: معهد العالم العربي، 1999.

شاهين، أحمد عمر. "موسوعة كتّاب فلسطين في القرن العشرين، الجزء الثاني". دمشق: المركز القومي للدراسات والتوثيق، 1992.

العودات، يعقوب. "من أعلام الفكر والأدب في فلسطين". عمان: د. ن.، 1976.

لوباني، حسين علي. "معجم أعلام فلسطين في العلوم والفنون والآداب". بيروت: مكتبة لبنان ناشرون، 2012.

"مذكّرات نجاتي صدقي"، تقديم وإعداد حنّا أبو حنّا. بيروت: مؤسسة الدراسات الفلسطينية، 2001.

Abdul Hadi, Mahdi, ed. Palestinian Personalities: A Biographic Dictionary. 2nd ed., revised and updated. Jerusalem: Passia Publication, 2006.

Descamps-Wassif, Sara. Dictionnaire des écrivains palestiniens. Paris: Institut du monde arabe, 1999.

Sidqi, Najati. “I Went to Defend Jerusalem in Cordoba, Memoirs of a Palestinian Communist in the Spanish International Brigades.” Jerusalem Quarterly no. 62 (Spring 2015): 102-109.