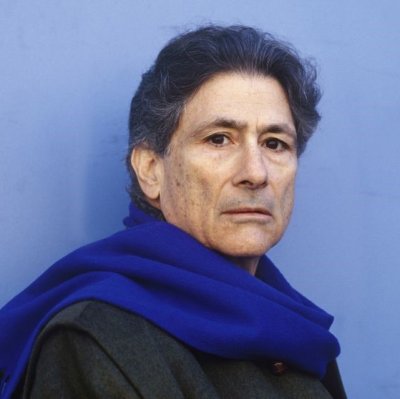

Edward W. Said

إدوارد سعيد

Birth of Edward W. Said in Jerusalem

1935

Said Studies at St. George's School in Jerusalem

1947

Said Studies at Victoria College in Cairo until His Expulsion

1948 to 1951

Said Leaves Jerusalem and Settles in Cairo with His Family

1948

Said Graduates from Northfield Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts

1953

Said Completes His Undergraduate Studies at Princeton University

1957

Said Completes His MA at Harvard University

1960

While Completing His Doctorate, Said Joins the English and Comparative Literature Faculty of Columbia University in New York Where He Remains Until His Death

1963

Said Earns a Ph.D. in English Literature from Harvard University

1964

June War

1967

In 1969, following the June War, Said Writes "The Portrayed Arab," His First Engaged Text

Arafat Addresses the UN General Assembly

1974

Said Translates Arafat's Speech for the UN and Meets for the First Time with Mahmoud Darwish and Shafiq al-Hout

13th Palestine National Council Meets in Cairo

1977

Said Is Elected to the Palestine National Council as an Independent Intellectual

19th Palestine National Council Meets in Algiers and Proclaims the Palestinian State

1988

Said Attends the Palestine National Council and Fully Endorses the Declaration of Independence

Said Receives an Honorary Doctorate from Birzeit University Amongs Other Prices over the Years

1993

Palestinian-Israeli Declaration of Principles Initialed and Approved

1993

Said Sharply Criticizes the Oslo Agreement

Death of Edward W. Said in New York

2003

The Edward Said National Conservatory of Music Is Established in Ramallah and Other Palestinian Cities

2004

Edward W. Said was born on 1 November 1935 to Wadih Said and Hilda Moussa in the Talbiyya neighborhood of Jerusalem. He had four sisters: Rose, Jane, Joyce, and Grace. He and his wife, Mariam Cortas, had a son, Wadih, and a daughter, Najla.

Said’s early education was in Cairo where his father had moved from Jerusalem in 1929 and established a stationary company. Said enrolled at the Gezira Preparatory School in the Egyptian capital. In 1947, the family spent much of the year in Jerusalem, and Said attended St. George’s School. Most of the family left Jerusalem in 1948, and so he enrolled at the new branch of Victoria College in Cairo (the main branch being in Alexandria). He was expelled from Victoria College in 1951, and his father sent him to the Northfield Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts, an elite Anglican preparatory boarding school from which he graduated in 1953.

Said completed his undergraduate studies at Princeton in 1957 and then earned an MA (1960) and a PhD in English literature (1964) from Harvard University. One year before formally completing his doctoral requirements, he joined the English and Comparative Literature faculty at Columbia University in New York City, where he began an illustrious career as a university professor. Columbia University served as his academic home for the remainder of his career, though he did accept several visiting scholar positions (at Harvard, Stanford, and Yale, among others).

Said is recognized as one of the world’s leading cultural critics. Michael Sprinker, who edited one of the first books on Said, noted that he represented the very ideal of the “cosmopolitan intellectual” that remains central to the humanities’ self-image today. Said contributed to focal debates in a vast number of social scientific disciplines, including history, sociology, anthropology, and area studies—particularly the study of the Middle East.

Said’s Orientalism and his subsequent books have helped to create entirely new fields of study, including postcolonial studies. With each book (about thirty in total, many of them translated to more than thirty-five languages) and his constant and sustained interventions as a public intellectual, he remained committed to a liberating humanism. In the dual role as a prolific scholar and a public intellectual, Said insisted that boundaries and barriers must be transgressed. He believed that intellectuals in modern society should speak “truth to power” and that the intellectual must insist on justice and give utterance not to fashion and passing fads but to real ideas and values, which cannot be articulated from inside a position of power.

Said was a nuanced and complex man. He is one of the few modern thinkers, along with Raymond Williams and Michel Foucault, to have critically interrogated the modernist project. Through both his literary work and his cultural criticism, he identified both the spectacular successes of modernity and its disastrous failures. In particular, he did not so much defend Islam or the Arabs as attack the reified notions of Orient and Occident. His primary concern was to delineate the sources of Western knowledge about non-Western societies. Like a mirror, Orientalism reflects Western power and its imperial appetite. To rescue the production of knowledge from colonial and imperial constraints, Said’s humanistic critique places primacy on subjective intuition and human individuality, rather than conventional wisdom. For Said, the real task of the intellectual is to advance human freedom and knowledge and resist the lures of power and specialization. The independent intellectual must universalize and give greater scope to the crisis confronting any nation at any given time by associating that experience with the suffering of others. It is precisely these moral concerns that Said invokes to probe issues pertaining to Palestine and the Middle East.

Said engaged with the idea of Palestine and its national movement (PLO) through various ways: (a) solidarity, (b) representation, (c) advocacy, and (d) critique.

The 1967 war pulled Edward Said out of his primary focus on English and comparative literature and in turn occasioned the rebirth of Said the Palestinian Arab. Hence, he found himself thinking and writing contrapuntally, animated by his Arab and American experiences. He renewed his connections with family members and friends who had joined the Palestinian national movement. At the invitation of the late Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, he contributed in 1969 an essay (“The Arab Portrayed”) to a special issue of The Arab World, a periodical that was published by the Information Center of the Arab League in New York. He described in his essay how the portrayal of the Arab as bloodthirsty and backward and the perception of the Israeli as hero and pioneer were inter-related. To this end, the Palestinian tragedy, “Arab lives and property taken, lost, or destroyed, Arab villages bulldozed out of existence, Arab resistance of any sort mercilessly liquidated,” had to be ignored.

In 1974, again at the suggestion of the Abu-Lughod, he was invited to translate Yasir Arafat’s speech delivered at the United Nations in 1974. In the process, he met for the first time the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish and Shafiq al-Hout, a Palestinian writer and the PLO’s representative to Lebanon. In 1977 Said was elected to the Palestine National Council (PNC) as an independent intellectual. He attended four sessions of the PNC, including the 1988 session in Algiers, which produced the Palestinian Declaration of Independence. He was not a member of any faction; he viewed his membership as an act of solidarity with his people and ultimately an affirmation of his Palestinian identity.

Said pursued his intellectual and political writings to construct what he dubbed in one of his essays as “permission to narrate” for the Palestinians, permission that had long been denied them. Through public engagements and multiple media outlets in the United States and elsewhere, he advocated for the right of Palestinian self-determination, producing an enormous impact as the major advocate for the Palestinian narrative in the West over several decades. But he was also a critic when needed. After fully endorsing the 1988 PNC declaration, he sharply criticized the PLO’s acceptance of the Oslo accords in 1993. Toward this end, he wrote columns in various Arab and international outlets.

Edward Said also served as music critic for The Nation and published several books on music. With the largesse of Palestinian philanthropists, he scouted and identified young Palestinian music talents for the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, which he co-founded with Daniel Barenboim.

Said passed away in New York after a long battle with leukemia. His remains were buried in Broumana, Lebanon. In 2004, one year after he passed away, the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music was established in Ramallah and other Palestinian cities, and the city of Ramallah named a street after him.

Edward W. Said received many awards, honors, and prizes, among them the Lionel Trilling Book Award (1976); Sultan Oweiss Award (1996–97); the Lannan Literary Prize for Lifetime Achievement (2002); and (with Daniel Barenboim) the Prince Asturias Award for Concord (2002). He received numerous honorary doctorates and was most proud of the one he received from Birzeit University in 1993. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a board member of International PEN.

Selected Works

“The Arab Portrayed”, in The Arab World. Special issue, 1969. New York: the Information Center of the Arab League. Published also in: Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, ed. The Arab-Israeli Confrontation of June 1967: An Arab Perspective. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1970.

Beginnings. New York: Basic Book, 1976.

Orientalism. New York: Pantheon, 1978.

The Question of Palestine. New York: Times Books, 1979.

The Word, the Text, and the Critic. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983.

After the Last Sky. New York: Pantheon, 1985.

Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993.

Representations of the Intellectual. New York: Pantheon, 1994.

Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

Out of Place: A Memoir. New York: Vintage Books, 1999.

From Oslo to Iraq and the Road Map. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.

Humanism and Democratic Criticism. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Sources

Ertur, Basak and Müge Gürsoy Sökmen, eds. Waiting for the Barbarians: A Tribute to Edward W. Said. New York: Verso, 2008.

Hovsepian, Nubar. “Edward Said: A Tribute.” Middle East Report, 33, 2003: 2–3.

Iskander, Adel and Hakem Rustom, eds. Edward Said: A Legacy of Emancipation and Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

Sprinker, Michael. Edward Said: A Critical Reader. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

Related Content

Policy-Program

Palestinian Declaration of Independence, 1988

Historic Undertakings For the Sake of Statehood