In the late nineteenth century, key figures in the fledgling Zionist movement provided the catalyst for “reimagining” Palestine as part of an ideology to justify Jewish colonization in the Holy Land. This effort at recasting Palestine in the consciousness of both Jews and non-Jews reached a critical threshold shortly after the publication of Theodor Herzl’s The Jewish State (1896) and imbued the Holy Land with a decidedly political edge. Although Palestine at the time was an Ottoman province with an overwhelmingly dominant Palestinian Arab demography, culture, and economic life, in the Zionist imagination it became associated with a wasteland, desecrated by its Palestinian inhabitants and desperately in need of redemption as a place with a Jewish character, as it was imagined to have been in the past. As part of this vision of Palestine as barren and neglected, a more aggressive conviction emerged, inspired by nationalist sentiments of the day, that the Holy Land was the rightful patrimony of the Jewish people. This idea of Palestine as the Jewish homeland has only intensified since the late nineteenth century and continues to dominate political and cultural discourse among Zionists inside the State of Israel and beyond. More poignantly, this imagined notion of Palestine as the land of the Jewish people has provided the inspiration for the politics of colonization, dispossession, and violence against Palestinians, historically and continuing to the present.

Imaginative Geography in the Service of Colonization

Edward Said, the celebrated Palestinian comparative literature scholar, was the first to develop the groundbreaking conceptual understanding of “imaginative geography.” He acknowledged that colonialism consisted fundamentally of the material impulse to seize the land of others, but he went further and insisted that colonizers were compelled to reinvent meanings about the lands they coveted and to justify why they were deserving of the places they sought to possess. In emphasizing the consciousness of the colonizer in the colonial impulse, Said drew from theorists ranging from Antonio Gramsci and E. P. Thompson to Michel Foucault and Max Weber and established a new foundation for comparing different cases of colonization. This comparative frame, anchored in the common impulse of imperial actors to justify why they were entitled to far-flung lands, revealed how colonial ventures in places as diverse as Algeria, Australia, the Americas, India, the Congo, and Palestine shared a basic, underlying thread. Said likened the imagined visions of colonizers to “the culture of Empire,” and in this way centered imagined geography in a more general theory of colonization for Palestine and beyond.

The Zionist imagination of Palestine reveals a steady repetition and amplification of a signature narrative. According to the narrative, Jews have expertise in science and engineering, and by returning to Zion they are able to improve and redeem the land more effectively than the local inhabitants. In the spirit of John Locke (1690), Zionists insisted that such superior abilities gave movement adherents a moral and legal right to the lands of Palestine. Promoted and popularized to this day, this discourse is perhaps best exemplified by the claim that Jews, inspired by the idea of a return to Zion, “made the desert bloom.” Thus, in the Zionist imagination, Palestine rightfully belongs to the Jewish people not only because of a holy covenant passed down from God, but also by virtue of Jewish initiative in “greening” what Herzl described as an “Arab-blighted countryside.” Proclamations of Palestine as the exclusive home of the Jews are as audible among Zionists today as they were at the outset of Zionism, borne out in 2018 by Israel’s “Nation-State Law” which affirms, among other things, that “the right to self-determination” in Israel is “unique to the Jewish people.”

From its very beginnings, Zionism confronted the problem that its imagined vision of Palestine was fatally flawed. Even early Zionists with first-hand knowledge of the Holy Land who were honest about the conditions there knew that; Ahad Ha‘am wrote caustically to others in the movement that the idea of Palestine as a desert, and Palestinians as “desert savages” was misguided.

The more intractable problem for the Zionists, however, was that Palestine for a millennium had ceased to be a dominantly Hebrew place. As a consequence, the Zionist movement was compelled to constantly “fix” the landscape in accordance with its idea of the Holy Land as Jewish—that is, it had to somehow align the real landscape with its imagined one.

Creation of Support for the Narrative

Three activities were especially salient to the Zionist movement in this process of meaning-making to intensify the Hebrew pedigree of the Holy Land: tree-planting, mapmaking, and archeological excavation.

Shortly after colonization of Palestine became the central aim of Zionism, the movement created the Jewish National Fund (JNF) in 1901. In addition to spearheading the purchase and settlement of land in Palestine, it also engineered a campaign of tree-planting in areas of Jewish settlement. The JNF chose conifers to create arboreal landscapes that could be considered as bearing a distinctly Jewish identity in contrast to the dominance on the land of the Palestinian olive tree. In this sense, tree-planting emerged as a weapon mobilized by Zionism to transform the meaning of the landscape itself from one decidedly Palestinian associated with olive cultivation, to one of pines now associated with a Jewish presence. Yosef Weitz, the longtime steward of JNF tree-planting, insisted that a landscape planted with conifers marked territory materially and symbolically as Jewish space. This project of afforestation has figured in the incessant Zionist claim of “making the desert bloom,” constituting an essential part of Zionist discourse to this day.

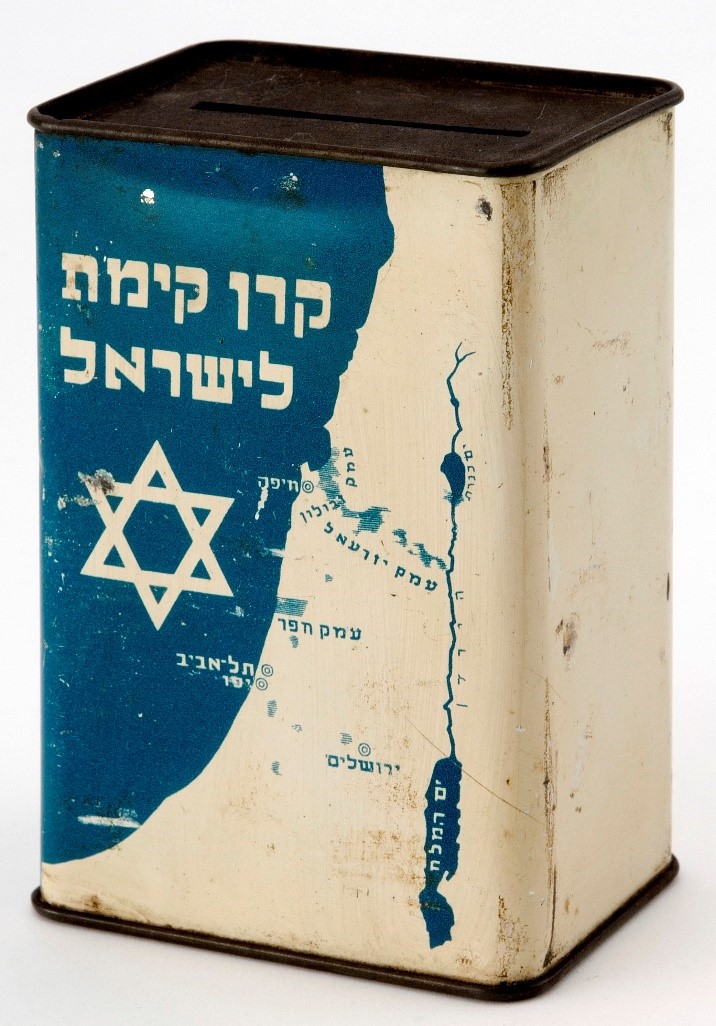

Similarly, the Zionist movement endeavored to create an alternative cartographic reality of Palestine. Some of the best examples of this reinvention are the maps made by the JNF during the Mandate period, above all, the maps for its so-called “Blue Boxes” that served as repositories for the collection of money for the Zionist movement. Bearing the title “Eretz Yisrael,” these maps convey a vision of Palestine as a Hebrew land and completely erase its Palestinian character. Zionists themselves considered these JNF maps to be legitimate instruments of “propaganda” in their campaign to encourage Jews to colonize the land of Palestine by presenting it as a largely blank slate broken only by the presence of Jewish settlements. Such practices of cartographic (mis)representation exist to this day, especially in maps produced by the Israel Tourist Board that project a territory to travelers called “Israel” in which Palestine and Palestinian places are submerged and even absent.

The third tool used by Zionists to fix the landscape was archeology. Zionists turned to archeology to reinforce the idea of the Holy Land as Hebrew land. For Zionists, the “return to Zion” intimated a once-vibrant Hebrew society in the Holy Land that Jews could restore. In 1920, the Zionist movement pioneered the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society (JPES) to spearhead the excavation of ancient Hebrew antiquities in Palestine, enlisting many of the most notable Zionist intellectuals in this effort. For Zionism and the JPES, Hebrew antiquities, once unearthed, were akin to a type of “land deed” testifying materially to the idea of Palestine as the land of the Jews and the rightful homeland of the Jewish people. By excavating Hebrew antiquities and bringing them to the land surface, Zionists were integrating the longstanding Jewish presence in Palestine into the texture of the landscape itself. This obsession among Zionists with archeology continues to this day, most notably by the large-scale but as yet unsuccessful effort to unearth the “City of David” in the Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan as proof of a once-glorious Kingdom of the ancient Hebrews.

The Palestinian Nationalist Narrative

If the Zionist movement evolved into an explicitly nationalist project of state-building tied to a vision of the Holy Land as a Hebrew space, so too did Palestinians develop nationalist visions of their own. In one sense, Palestinian nationalism evolved from the same historical crucible that inspired other oppressed groups to pursue their aspirations for an independent identity and equal rights through nation-building. At the same time, Palestinian nationalism forged a distinct identity as an ideology and movement of resistance to Zionism, based on a sense that the aims of Zionism threatened the existence of Palestine itself. By 1904–14, Zionist settlement was already provoking fear among Palestinians. Even Zionists such as Yitzhak Epstein (1907) acknowledged that land purchases by Zionist settlers had resulted in evictions of Palestinian tenant farmers under the auspices of the slogan “Hebrew Land, Hebrew Labor.” What ensued was a burgeoning radicalism among the Palestinian peasantry that emerged as a flashpoint for Palestinian national aspirations. Significantly, the proliferation of a Palestinian Arabic press after 1908 played a decisive role in circulating stories of these rural abuses and spreading this newly forged consciousness of resistance throughout the population. Two newspapers in particular emerged as fierce critics of Zionism and staunch defenders of Palestinian national rights. One was al-Karmel, established in Haifa in 1908; the other, launched in Jaffa in 1911, was Filastin. Complementing the Palestinian press was an array of intellectuals, notably Khalil al-Sakakini, who also became promoters of this emerging Palestinian national consciousness.

A Zionist Narrative Sustained through Force

Thus, while Zionism was seeking to transform Palestine into a Jewish state based on a vision of the Holy Land as Hebrew land and the rightful patrimony of the Jewish people, Palestinian nationalists were resisting this state-building project, arguing that Palestinians had been living in their homeland for the past 1,500 years. Both visions of nationalism and belonging persist to this day, but the idea of Palestine as the longstanding and enduring homeland of the Palestinian people continues as an inspiration for resistance. By contrast, what was an imagined geography of Palestine as a Hebrew space has given way to an actual condition of colonization and Jewish settlement on the land, built upon a foundation of conquest and complemented by ongoing exercises of power, domination, and force.

Nevertheless, this actual condition of conquest, colonization, and settlement remains incomplete. With varying degrees of success, Palestinians have remained steadfast on the landscape, motivated at least in part by nationalist impulses and a sense of their enduring presence on the land. In response, the Zionist movement and its modern-day descendants have resorted to the second, more brazen type of “fix” to remake the Palestinian landscape as Jewish space in the way they imagine it. These efforts to align the actual landscape more closely to the imagined one aim at purifying the land of the Jewish people by forcibly removing Palestinians from the land.

The defining example of this type of fix occurred in 1947–49 with the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians from what became the State of Israel and the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages, many buried and erased under afforestation projects of the JNF. In addition to this singular event, however, ongoing campaigns aim at ridding the landscape of its Palestinian presence. Some campaigns dispossess Palestinians by means of the law, a kind of warfare pursued through legal institutions perhaps best described as “lawfare,” that seeks to remove Palestinian presence on the land by eliminating Palestinian rights to landed property. Similar to lawfare is an even more overt kind of violence in the form of home demolitions which occur through a hyper-legalized system of building permits (generally denied to Palestinians) and classifications of Palestinian homes as non-conforming and thus illegal.

Another measure used to rid the landscape of its Palestinian presence is the brazen uprooting, burning, and destruction of Palestinian croplands. That affords an opportunity to glimpse a more direct impact of the Zionist imagination on Zionist actions to realign the landscape. By destroying Palestinian farmlands, Zionists deprive Palestinians of the ability to feed themselves—a first step in forcing their removal from their land, thus making the landscape more compatible with the Zionist imagined geography. In the Zionist imagination, Palestinians cannot act purposefully or independently on the land.

That imagination was expressed matter of factly by an Israeli teenager from a Jewish settlement who was asked by legal geographer Irus Braverman why she and her friends had burned and uprooted Palestinian olive trees in the village of Sinjil. Her reply—“I have nothing against the trees, this is about the land—it’s our land, not theirs”—affirms Edward Said’s argument that the imagination is not simply embedded in the psyche but is part of a very real material impulse.

Abu El Haj, Nadia. Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Benvenisti, Meron. Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Braverman, Irus. Planted Flags: Trees, Land and Law in Israel/Palestine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Fields, Gary. Enclosure: Palestinian Landscapes in a Historical Mirror. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.

“Israel Tourist Map.” https://israelmap360.com/israel-tourist-map

Khalidi, Rashid. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Said, Edward. “Invention, Memory, and Place.” Critical Inquiry 26, no.2 (2000): 175–92.

Yiftachel, Oren. Ethnocracy: Land and Identity Politics in Israel/Palestine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Related Content

Institutional Colonization

5th Zionist Congress Is Held in Basel

1901

26 December 1901 - 30 December 1901